“A subject for Thanksgiving should be the fact that the base-ball season is over, and the space in the newspapers devoted to that sport can now be used for original poetry.” ~ The Inter Ocean (Chicago), 1881

Here’s one from 1910:

The Base Ball Season Is Over

The baseball season is over

The players have all gone home

They have done their best

To down the rest

And place our team at the dome.

The baseball season is over

Our summer pleasures are done

They’re all “put out”

Without a doubt

And they’ve made their last, lone run.

The baseball season is over

There is grief in the small boy’s heart

As he thinks of the days

When he saw the good plays

That our team made like a dart.

It goes on for a few more verses and you can read the entire poem here if you like. It ends like this:

The baseball season is over

Next year will soon roll around

And we’ll get a good start

And dart like a lark

To the head of the column, so long.

This poem appeared in a Concordia, Kansas paper in 1910 and maybe “around” really did rhyme with “long” back then. It seems like the author – who is never named – ran out of poetry steam by that last line.

The poem was a tribute to the Travelers, a minor league team that made its debut in Concordia that year … and folded for good the next.

I liked the poem and thought that was the story I wanted to tell you. But, there is one bit of Concordia Travelers business that needs clearing up – and, I promise you, I’m not happy to do this.

Two players on that 1910 team went on to have short stints in the majors.

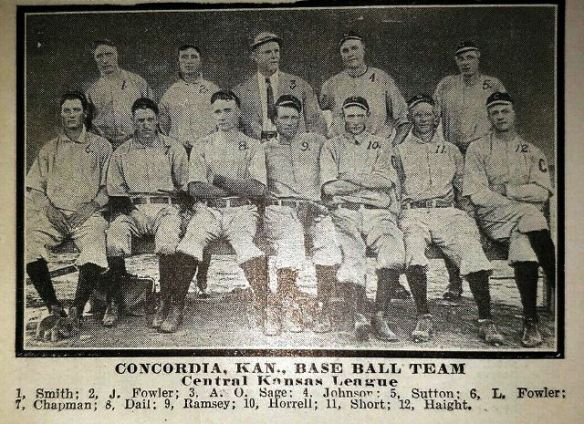

Concordia Travelers, 1910. Chick Smith, back row, far left. Harry Chapman, front row, second from left.

Chick Smith, a reliever (something of a rarity at the time), spent five games with the Cincinnati Reds in 1913, pitching 17.2 not-bad innings.

Catcher Harry Chapman played 147 big league games here and there with the Chicago Cubs, Cincinnati Reds, St. Louis Terriers (Federal League), and St. Louis Browns between 1912 and 1916.

And, here is where our story turns to Chapman.

Chapman, born in Severence, Kansas in 1885, starts his pro career with the Concordia Travelers, showing up midway through that 1910 season. He makes his debut on July 9 and singles in a 6-0 loss to Salina.

He is known for his strong throwing arm – a “rifle-shot whip” as one writer described it – and smart “under pressure” catching. While his major league career was spotty, he becomes a star in the minor leagues.

Trivia Alert: Chapman’s big league career is unnoteworthy but for a tiny thing. As a Cub in 1912, he is bundled in the trade that sends Joe Tinker to the Reds. (Tinker demanded the trade, because he refused to play under his nemesis – new Cubs manager Johnny Evers.)

Back in the minors in 1913, Chapman is part of the Atlanta Crackers that win the Southern League championship. His catching, The Atlanta Constitution noted at the time “was one of the most vital, if not the most important, factor in the team’s final dash for the pennant when they won 21 out of the last 23 games played.”

Chapman was, The Constitution later noted, “a deadly pegger and it was on rare occasions that a runner got away from him.”

Chapman spends the 1914 and ’15 seasons with the St. Louis Terriers of the renegade Federal League and plays 18 games with the St. Louis Browns in 1916, before slipping back to the minors for good.

He finishes his career in 1917 with the minor league Arkansas Travelers (no relation to the by-then, long-gone Concordia, Kansas Travelers).

And, here’s where some clearing up must be done.

The internet suggests that Chapman was a casualty of World War I, an Army soldier who was one of eight major league players who died during the war. He was serving in the Army, Wikipedia and other sites report, when he died of the flu during the pandemic in October 1918.

That second part is true. He did die of complications of the flu. But, the first part – the army, war part? It appears to be a myth. A myth that, I must admit, I, too, perpetuated, in this story I wrote in 2017 about baseball players who served during World War I.

The truth about Chapman, I’ve discovered, is much blurrier and, I think, much sadder. But, I think it deserves to be told.

And it is this.

In January 1918, the Little Rock papers eagerly announce that Chapman – affectionately known as “Chappie” – will be back behind the plate for the Travelers come the springtime. While some players were expected to be drafted, the sportswriters assured readers that the popular Chapman – in his 30s with a “dependent wife” – was over “draft age.”

Not long after, local sportswriters report that Chapman has been seriously ill through the winter and is retiring immediately to live on his farm in Missouri. There would be no Chappie on the Travelers after all.

That’s the last we hear of Chapman. Until October 1918.

Chapman dies on October 21, just a few days short of his 33rd birthday, in a Nevada, Missouri hospital, from a pneumonia brought on by Spanish Influenza – that other pandemic that we were so sure could never happen in this country again.

No military service is mentioned. Not in his detailed obituaries that appear in local Missouri and Kansas papers and in other papers in towns and cities where Chapman once played. Not on his death certificate. Not on his simple gravestone. Not in any World War I military records that are readily available online.

And, things get even blurrier.

That hospital, in Nevada, Missouri, was State Hospital #3, one of the state’s “insane asylums.” His death certificate notes that he had been a patient there for 10 months.

A few weeks after his death, both Little Rock papers spill Chappie’s “secret.”

“Now that ‘Chappie’ is gone, it is permissible to reveal the fact that a mental derangement was responsible for the fact that he was not with the Little Rock club last season. This derangement developed acutely last spring and the unfortunate victim died in an asylum at Nevada, Mo. His affliction had not been revealed because there was hope that he might recover and it was desired to save him from embarrassment should he ever be able to return to baseball. He showed no sign of insanity while he was with the Little Rock club, although he was subject to spells of melancholy at times.”

– Daily Arkansas Gazette (Little Rock), 11/1/1918

Little Rock’s Arkansas Democrat tells virtually the same story, adding:

“[H]is condition became such after the close of the 1917 season that it was thought best to send him to an institution where he might be treated with success.”

The Democrat continues:

“Chapman was what is known as a ‘head’ player. He was cool at all times, was a master at handling pitchers, and got out of them all that was in them. When he came to bat at a critical period in the game it was not he, but the pitcher he faced who was worried.”

I’m not setting the record straight here to embarrass or impugn Chapman’s memory.

But, it bothers me that his story – his truth – has become twisted. Was it a simple mix-up? Harry Chapman was a common name back then. You can find oodles of WWI draft registration cards of other Harry Chapmans online. Or, did someone believe that our Chapman needed a better ending?

That’s what bothers me. The notion that a mental health condition is something to be ashamed of, something to hide. The Arkansas Travelers and the sportswriters of the day initially hid his condition out of respect. I get that. But, why did someone feel the need to twist things and make him into a war “hero” in death?

Harry Chapman died on October 21, 1918, of complications of pneumonia and the “Spanish flu” while a patient at State Hospital #3, in Nevada, Missouri.

Imagine if the world in 1918 had a vaccine that could have stopped the pandemic in its tracks.

Perhaps, Harry Chapman would have recovered. Perhaps, he would have played baseball again.

Perhaps, his story would have turned out different.

But, there’s no shame in the story that he had.

Enjoyed reading your latest.

Thanks, Mere!

Thank you for this story. Even today mental illness carries with it a certain degree of stigma that makes people uneasy to speak openly about it.

Yup …from pandemics to the stigma of mental health illnesses … some things haven’t changed much at all, have they?

Thanks for a great read and thoughtful perspective, Jackie. Let’s hope that 100 years from now the secrecy and stigma around mental illness and the need for supports is another history lesson.

Not sure we’ve progressed all that much. Would suspect there’s quite a few notable sports figures whose mental illnesses were hidden from public view.

Hey Jackie…Great research on your part! Great detective work. It’s so easy to take what we read, on wikipedia or elsewhere as the bottom line truth which is not always the case as you have discovered here. Hope all’s well.