Warning: Editor/Husband has been sick and in bed since Christmas Eve. This means that I am a) most likely highly contagious, and b) posting without an editor. If you cut out now, I’ll understand. (I’ll be deeply hurt, but I’ll understand.) (Sort of. I’ll sort of understand.)

Someone found this blog by searching for this:

Shoeless drunk?

First of all, I’m very disappointed in you, Internet. Second of all, I wonder what that person was looking for?

I searched for “shoeless drunk” on the Googler and I didn’t find me. (What I did find was disgusting, with the exception of a few movie stills from 1967’s “Barefoot in the Park,” starring Robert Redford and Jane Fonda.)

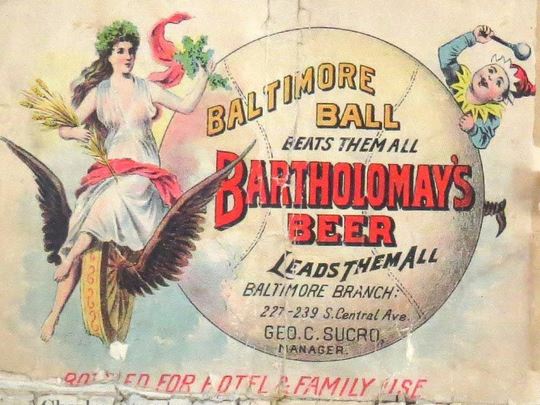

In writing about baseball, there is always Shoeless Joe Jackson and quite a number of drunks, so maybe it wasn’t such a stretch after all that someone landed here.

Embed from Getty ImagesShoeless Joe Jackson, 1919.

Shoeless Joe may have never really been shoeless, as he occasionally denied the story of ever playing in his stocking feet in the minor leagues. But, he also occasionally said the story was true, so who’s to know?

Also, no distraught kid ever tugged his sleeve outside a Chicago courthouse and said, “Say it ain’t so,” when the White Sox were found to have tossed the 1919 World Series.

But, Damon Runyon did say this: “Even when he’s trying to throw a Series, Shoeless Joe Jackson can still hit .375.”

This led me to wonder when Joe Jackson died.

December 5, 1951. He was 64 and several hundred people attended his funeral in Greenville, South Carolina.

This led me to wonder, in a tangent I can’t explain, when Willie Mays hit his first home run.

And, it was 1951, too. May 28.

As most baseball fans know, Mays’ first home run was also his first hit as a big leaguer. He had gone 0-for-12 in his first three games. This was his first home at-bat at the New York Giant’s Polo Grounds.

The home run was, The New York Times said, “a towering poke that landed atop the left-field roof.”

The homer, off the Boston Braves’ Warren Spahn, wasn’t enough. The Braves defeated the Giants that night, 4-1.

Embed from Getty ImagesWillie Mays.

Historian Charles Einstein shared these quotes from that game:

“You know, if that’s the only home run he ever hits, they’ll still talk about it.” ~ Russ Hodges, who called the game on radio that night. (And, look … he’s right!)

“For the first 60 feet it was a hell of a pitch.” ~ Spahn, who said he threw a fastball as his first pitch to Mays because he was sure Giants’ manager Leo Durocher had told Mays to lay off the first pitch. (Durocher hadn’t.) Or, maybe it was a curve ball, which scouts said Mays couldn’t hit, as Spahn remembered it in 1973.

“The ball came down in Utica. I know. I was managing there at the time.” ~ Lefty Gomez (This would be an even better quote if Gomez actually had been managing in Utica at the time. He hadn’t. But, it’s still pretty good.)

“I never saw a f*ing ball get out of a f*ing ball park so f*ing fast in my f*ing life.” ~ Leo Durocher

I can’t show you that home run, of course, because the Internet and MLB.TV hadn’t been invented yet.

Embed from Getty ImagesWarren Spahn.

Mays would hit 17 more home runs off of Spahn including one in the 16th inning of a game on July 2, 1963.

By 1963, the Giants were in San Francisco and the Braves were in Milwaukee.

Mays’ walk-off home run off Spahn in the 16th ended one of baseball’s most awesome pitching performances: 42-year-old Spahn, for the Braves, and 25-year-old Juan Marichal, for the Giants, threw a combined 428 pitches through those 16 innings.

“It was a screwball,” Mays said following the game, “But I guess Warren was getting kind of tired.”

“Yes, I was tired,” Spahn said, “But, I wish Willie had been tired, too.”

I can’t show you that home run either. But, here’s Mays and Marichal talking about it:

“Ok, let me see what I can do about it.”

(Giants fans of a certain age will insist that Willie McCovey’s foul ball in the bottom of the 9th was actually inside the foul pole and should have been the home run that ended the game. McCovey will tell you that, too. But, like the Internet, batting helmets, and wild card teams, instant replay hadn’t been invented yet.)

And, so here it is Boxing Day and Editor/Husband is still feeling crummy and is fast asleep in the room next door. He will dislike this post when he sees it, because it just wanders around pointless.

Just sitting here thinking about Willie Mays.